Engaging with SCO as a dialogue partner does not mean sliding back into the arms of Russia and China, like during the administration of Rodrigo Duterte.

But it is a pragmatic move to expand the country’s engagement to gain more economic and political benefits to advance the Philippines’s interests.

It would make Philippine foreign policy more independent and could not be accused of pro-Western bias as tensions in the West Philippine Sea escalate.

It could help the Philippines in terms of fighting Islamist militancy which SCO member-states also have problems with.

The SCO could also bridge the gap between the Philippines and China in managing maritime disputes in the South China Sea.

The SCO is the largest regional grouping, in terms of geography, covering about 80 percent of Europe and Asia.

About 20 percent of the world’s GDP and 40 percent of the global population are part of the SCO, including China, India, and Russia, which are also members of the emerging economies BRICS Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa.

Thus, the Philippines stands to benefit from such regional grouping to advance its economic interests, apart from Asean, APEC, and the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework.

The ongoing process of fundamental structural transformation of the existing world order, the formation of a new configuration of international relations, and the worsening global political and economic problems dictate the need for better cooperation among regional structures, like the SCO and Asean.

SCO and Asean are geographically connected and could help strengthen peace and stability in the bigger Asia-Pacific region.

The two organizations have a mutual interest in cooperating in the areas of trade, investment, tourism, and culture.

SCO and Asean are not like AUKUS and QUAD which are primarily a military alliance with an “exclusive” format and target particular states that could fuel regional tensions.

In this context, it seems logical to develop cooperation between Asean and SCO to enhance coordination in to fight against Islamist extremism, terrorism, criminality, and drug trafficking and, at the same time, address pandemic recovery issues and hunger.

Taking into consideration these facts, Asean should also look at the motive behind the US anti-SCO rhetoric as regional attitude toward Washington has been changing and the US could lose its influence and well-established control system that was set up after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1990.

Recent surveys done by a Singapore think tank showed 50.5 percent and 49.5 percent in favor of China over the US as the dominant force in the region.

It is not helping the US when it continues to discredit SCO when most in Asean see a polarization to make states in the region choose between the US and China.

Asean must maintain its cohesiveness and centrality and take the driver’s seat in moving toward a direction where it wants to go, not dictated by any outside power, including the US and China.

Its voice must be heard loud and clear in the United Nations to assert its rights and views.

As part of Asean, the Philippines must give serious thought to engaging with SCO in the field of transnational crime by exchanging and sharing best practices in fighting separatism, terrorism, and extremism.

The Philippines shares with many states in SCO and Asean the same problem with ISIS-linked local militant groups.

Cambodia and Myanmar, with similar but bigger problems with separatism, are already SCO dialogue partners.

Manila should grab the chance to become a dialogue partner or even become a member like India, Pakistan, and Mongolia which also have vibrant relations with the US and the West.

Moreover, engaging with SCO would help balance the country’s relations with the US.

That is a real independent, non-aligned foreign policy.

Why the Philippines should be wary of NATO’s expansion into the Indo-Pacific region

The Philippines should learn its lessons from other ASEAN states. It should have a more independent foreign policy and be less dependent on the West. It is unclear if the US and NATO would be there if conflict erupts.

ALERT: China Daily’s new Tiktok account amasses millions in engagement despite having no content

After TikTok banned the state-run China Daily’s account from its platform, a new account with a similar name and logo has surfaced, already amassing hundreds of thousands of followers and millions of likes despite having no content posted.

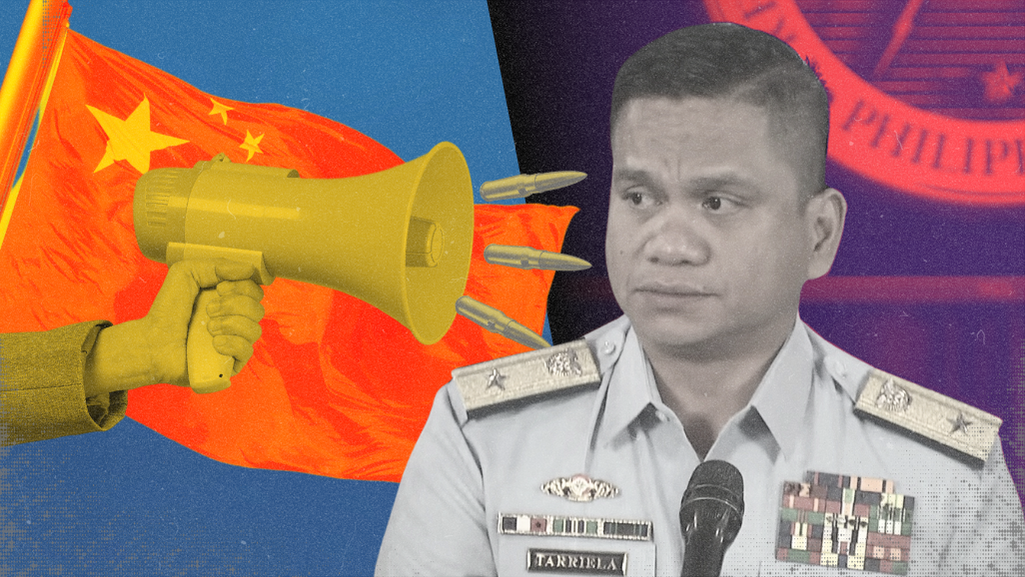

IN-DEPTH: Pro-China opinion writers escalate online attacks vs Coast Guard spokesman

“Tainted source, PMA reject, CIA operative, US dog.” These are some of the ad hominem attacks lobbed against Commodore Jay Tarriela by pro-China propagandists and trolls.