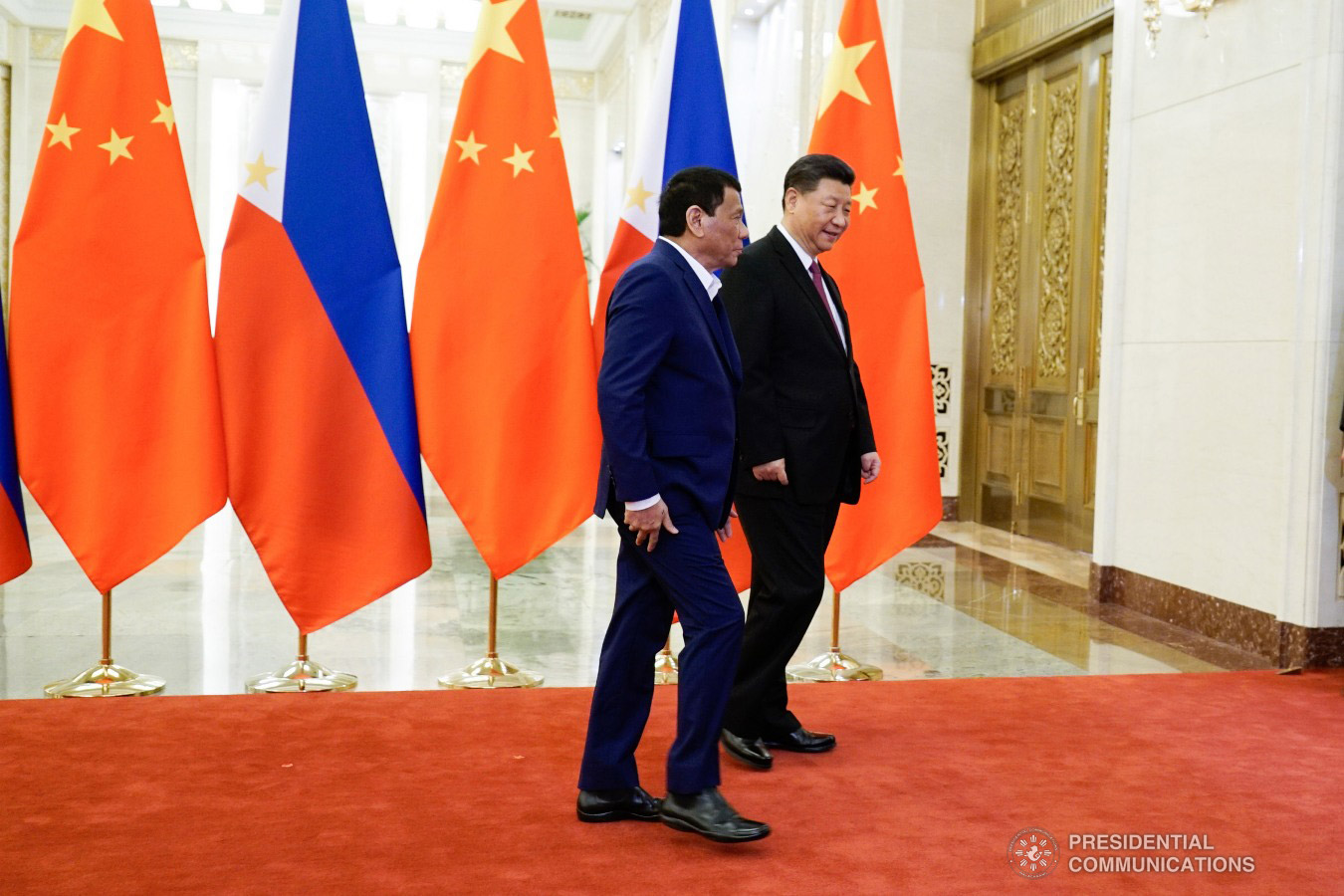

President Rodrigo Duterte is accompanied by Chinese President Xi Jinping inside the Great Hall of the People in Beijing prior to their bilateral meeting on April 25, 2019. KING RODRIGUEZ/PRESIDENTIAL PHOTO

When China hosted its first Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation in May 2017, two important Southeast Asian leaders were not invited to the summit, dubbed by the Western press as Beijing’s bid to reshape a new world order.

Chinese leaders ignored Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and the leader of Thailand’s military junta, Prayut Chan-o-cha, after the two leaders offended Beijing’s policies, including on the sensitive South China Sea dispute, where the two countries were not parties and did not have territorial claims.

The snub was a very swift retaliation to show how powerful and influential Beijing has become in just a generation from the deadly and brutal Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. It has overtaken Japan and larger economies in Western Europe to challenge the United States’ global leadership in the military, economic and development assistance spheres.

Wang Xiaotao, deputy head of the National Development and Reform Commission, described the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) as an attempt to build “a more open and efficient international cooperation platform; a closer, stronger partnership network; and to push for a more just, reasonable and balanced international governance systems.”

However, some people have warned that the BRI could become China’s tool to dominate and spread its political and strategic interests around the world. Poorer economies in Latin America, Africa, Central and South Asia and Eastern Europe might become too dependent on Chinese official development assistance (ODA) and generous but expensive loans, and might fall into a debt trap, like Ecuador and Sri Lanka.

In April this year, at the second BRI summit, Singapore and Thailand were back in China’s good graces as Beijing sought to further expand its economic and military influence. “Little Chinese cities” mushroomed and blossomed across Southeast Asia – in Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar and the Philippines. Offshore gaming operations, construction, retail, tourism and leisure, and agricultural ventures spread rapidly in most parts of Southeast Asia to feed the growing appetite of China’s state-controlled and private investments for growth and profits.

Roughly 100 million Chinese awash with cash travel abroad as tourists and students, reaching as far as Australia and the United Kingdom, making many governments nervous and assess the sudden interest of Chinese nationals to travel, study, work and open businesses in other parts of the globe. What became more worrisome for some of these states was the Chinese government’s obvious strategy to involve ordinary Chinese nationals in intelligence-gathering operations. This was proven by a few cases, such as in Poland involving a Chinese worker connected with Huawei, Beijing’s dominant telecommunications company.

Countries around the world are starting to push back against China’s hegemonic tendencies. In a sudden twist when a new government came to power in Sierra Leone, President Julius Maada Bio cancelled the $300-million airport project outside the capital Freetown, after the World Bank and International Monetary Fund warned the Chinese loan would be an unnecessarily big burden on the West African country.

This was the first case of a Chinese-funded mega-project scrapped in Africa, where Beijing has poured more than $130 billion in loans to build transport, power and mining projects in the resource-rich but poor continent.

Closer to home, some Southeast Asian governments have started to feel China’s creeping economic and military influence in the region, and have quietly and politely began pushing back on China.

Thailand has recently proposed a tight immigration policy, requiring more than 2 million foreign workers and long-time foreign residents, mostly Indians and Chinese, to report as often as possible for security reasons, despite opposition from the private sector over fears of its impact on skilled workers and on tourism revenues.

Experts and journalists, at a recent Japan-Asean Media Forum in Bangkok, suggested that fears over China’s growing influence along Thailand’s northern borders, which could be affecting the long-running ethnic-based insurgency with Kachin rebels, had forced the unstable but resource-rich Southeast Asian country to open up and engage with countries like Japan and the United States.

Indonesia and Vietnam are traditionally anti-Chinese, although the Vietnamese Communist Party and China’s Communist Party have excellent relations. Indonesia’s tight control over the narrow Straits of Malacca is a big factor why Beijing has not been friendly with Jakarta, and some Chinese fishing boats were blown into pieces for poaching into Indonesian waters.

Malaysia has asked to renegotiate some big funding given by China during the time of Najib Razak, but the new leader, former prime minister Mahathir bin Mohamad, could ignore the fact that China is the country’s trading partner and source of investments and tourist arrivals. Some deals believed to be onerous will be restructured, but it seems there will be no decisions to get new contractors. Japan has emerged as the favorite to replace Chinese contractors in India, Indonesia and the Philippines.

Japan and India are the two big regional powers with unsettled territorial disputes with their respective neighbors, but are careful not to create further tension in the region. Together with the United States and Australia, these four countries are leading efforts to subtly contain Chinese influence through a new Indo-Pacific strategy.

In the collective effort to push back on China, enlisting the 10 Southeast Asian countries as a single bloc may not succeed, however. The economies of Brunei, Cambodia and Laos are too dependent on China and the Philippines’ position is vague. Rodrigo Duterte has brought the Philippines closer to China, attracting investments and aid at the expense of its strategic alliance with the United States. Only the security sector appears loyal to the 1951 Mutual Defense Treaty with Washington.

Rodrigo Duterte’s China policy will be put to test this week as the president embarks of his fifth visit to Beijing. It will be the ninth meeting between Duterte and Chinese leader Xi Jinping. The Filipinos eagerly await the meeting.

Will Duterte find courage to raise the international decision in The Hague and convince China not to further delay the conclusion of the legally binding regional Code of Conduct? All eyes are on Duterte if he will join the bandwagon on push back against China or cow into submission, like other smaller and poorer Southeast Asia countries.