By Winona Sadia

Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism

Learners with special education needs require

face-to-face instruction but are vulnerable to the coronavirus disease.

Parents and teachers have no choice but to make distance learning work.

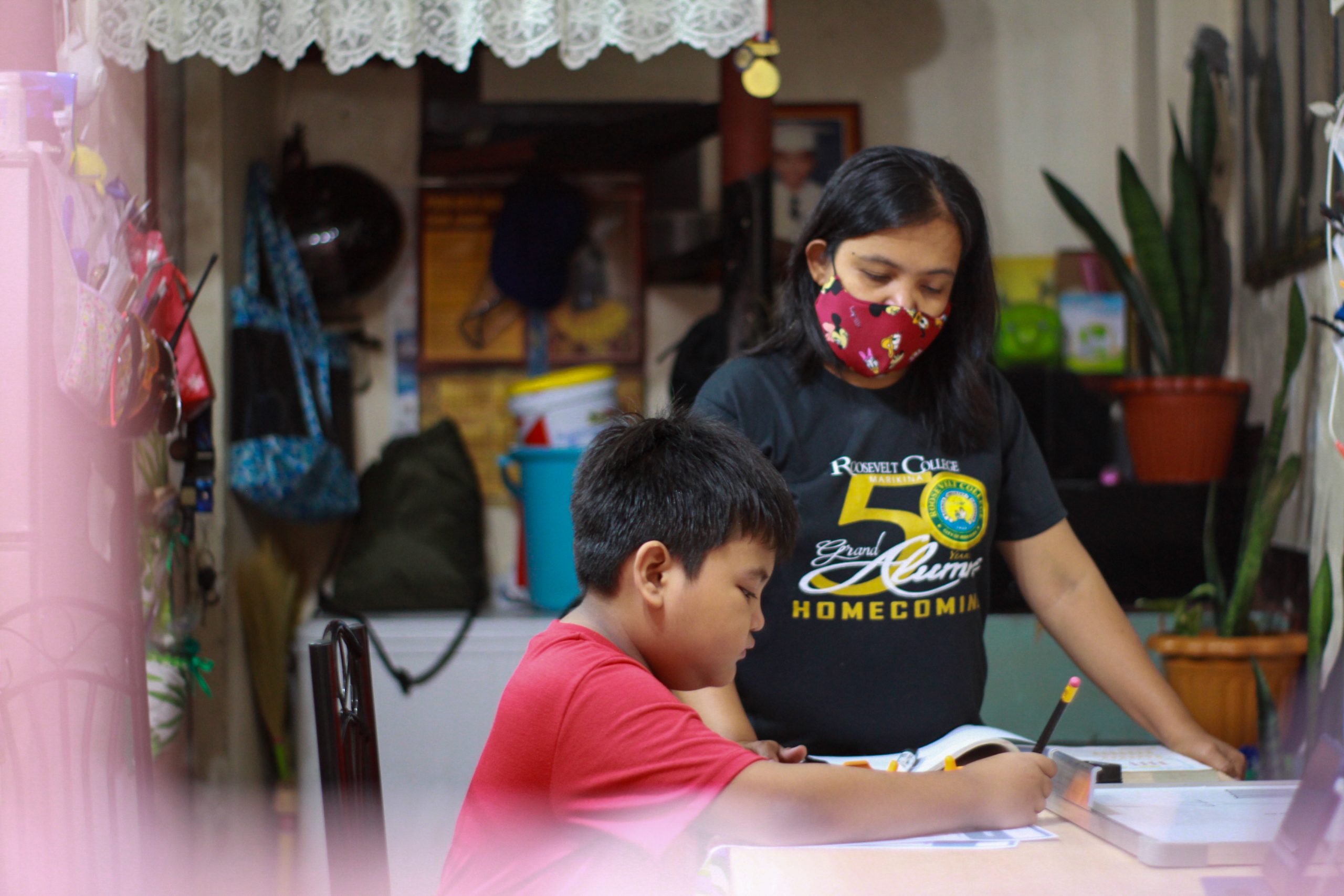

Elena Elpedez makes the most of the months-long lockdown by helping Enzo review his previous lessons. | Winona Sadia / PCIJ

As the clock ticked closer to 10 a.m., Elena Elpedez cleared the dining table to make way for her son’s online class simulation. Ten-year-old Enzo, who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder orADHD, has the entire makeshift study area for himself for a good hour. Excited, Enzo set up his Zoom account to meet up with his classmates and teachers, albeit virtually.

Despite the difficulties of distance learning amid the coronavirus pandemic, Elena did not think twice about enrolling her bunso (youngest child) this school year for special education or SPED at Parang Elementary School in Marikina. It was better, she said, than letting months pass without Enzo learning anything.

Elena left her business process outsourcing job in 2015, as soon as she realized the need to supervise Enzo’s schooling and therapy. She then put up a printing business at their house to augment her income.During the lockdown, Elena recycled reviewers and worksheets from customers to refresh Enzo with what he had learned the previous school year.

Elena prints out recycled worksheets to help Enzo continue learning during quarantine. | Winona Sadia / PCIJ

“Para ma-instill sa kaniya na dapat continuous pa rin ang pag-aaral niya. Ayaw ko kasing isipin niyang bakasyon lang siya, baka matagal ko na naman siyang mapapayag mag-school (I wanted to instill in him that learning should be continuous. I don’t want him to think it’s just a long vacation. It might take time to convince him to go back to school),” she said.

The 44-year-old mother of two was worried over their internet connection after the school held simulation classes ahead of the opening on Oct. 5.She’s keeping her fingers crossed that Enzo and his kuya (older brother) Edrei, an 18-year-old Grade 12 student,would have opposite class schedules so they won’t use the internet at the same time.

The problems of SPED parents and teachers go beyond weak internet connections, however. Physical interaction with teachers is a cornerstone of SPED, and experts and stakeholders are still debating whether to push face-to-face classes or settle for distance learning. One thing is sure: parents like Elena will have to pull all stops to make everything work, if they don’t want their kids left behind.

(See related story: Will distance learning work? Parents, teachers not so sure)

But Elena is not so confident in becoming Enzo’s teacher.

“Titingin ako sa books niya ngayon at ipapabasa sa kanya. Kung ano `yung pagkabasa [at] pagkakaintindi namin, `yun na `yun,” she said. “Hindi katulad ng teacher, may sarili silang style, may mga visual aid pa sila, which is hindi talaga magagawa ng parent (I will look at the books and ask him to read them. How we read and understood them, that’s it. Teachers have their own style, they have their own visual aids, which parents don’t),” she said.

Elena converts their dining table into a makeshift study area for Enzo, who begins schooling at Parang Elementary School on Oct. 5. | Winona Sadia / PCIJ

Exception for SPED learners?

SPED enrollment has always been low. Genevieve Caballa, executive director of the Alternative Learning Resource School Philippines (ALRES-Phils) – a school offering SPED and therapy programs – said that 97 percent of learners with disabilities were not in school. Enrollment has not improved for more than a decade, she said.

Data from the Department of Education (DepEd) showed that of more than 5 million Filipino children with disabilities nationwide, only 1.4 percent or more than 71,000 non-graded learners were enrolled for the upcoming school year as of September.

Former education secretary Bro. Armin Luistro called for face-to-face classes among learners with special education needs, or LSENs, despite the pandemic.

“SPED should continue and it has to be face-to-face. There are only a few students and they need the equipment and special teachers in the schools. Barangay (village) leaders and DepEd should work together on it,” Luistro told the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ).

Fernan Gana, president of the Quezon City Federation of Parents and Teachers Associations, said this was easier said than done.

“Tama `yung rekomendasyon [pero] siguro, pag-aralan lang `yung protocols [at] kung paanong iiwasang magkahawaan ‘yung mga bata. Alam naman nating mas vulnerable sila, lalo na `yung mganasa SPED school (The recommendations are correct but the protocols should be studied to prevent kids from infecting one another. Those who are in SPED school are more vulnerable),” he said.

But for Reading Association of the Philippines President Frederick Perez, SPED institutions might have to consider halting classes altogether.

“Sorry to the SPED schools but I don’t believe that special education will be meaningful and fruitful at this time. Maybe next year. They (LSENs) need a lot of physical contact,” he said.

‘Face-to-face learning ideal, but safety first’

Caballa would rather stick to distance learning, cautioning against resuming face-to-face classes for LSENs.

“Many of them are immunocompromised, so they are more at risk than neurotypical children. [We] don’t want to endanger learners. They could get easily infected,” she said.

Caballaargued that halting school altogether for SPED learners would mean depriving them of their right to continuous education.

“Children have a critical window for development and learning opportunities. If you miss that, there’s no turning back,” she said.

The SPED expert also warned against“regression,” which she said was common among learners with disabilities.

Neurotypical learners, or children with no intellectual or developmental disorders, were less likely to regress even with long breaks from studies, as they have other options to continue learning, she said.

“For learners with disabilities, if they don’t study or are not given just a little stimulation, they easily regress academically and behaviorally,” Caballa said. “The intervention we’re looking at is really empowering parents. Parents are the key.”

According to DepEd’s Basic Education Learning Continuity Plan, face-to-face instruction for learners with disabilities would be allowed only in “very low-risk areas” such as geographically isolated, disadvantaged, and conflict-affected areas with no history of Covid-19 infection.

However, teachers and learners should be living in the vicinity of the school. Face-to-face classes for LSENs, DepEd said, must undergo risk assessment and adhere to strict health protocols.

Redefining learning

Caballa said the way to help LSENs cope with the new normal in education was for parents and teachers to “redefine learning.”

When SPED classes opened at her school on July 13, teachers saw the need to engage the household in online and offline learning activities.

“It’s not just paper and pencil. It’s integrated in home routines. In cooking, for example, we incorporated functional math and reading, reading a recipe, measurement, procedure,” Caballa said.

SPED teachers must also make it a point to keep the screen time within the “ideal” one to two hours per session, she said.

Some of Enzo’s artworks are displayed on the walls of their house in Marikina. | Winona Sadia / PCIJ

The new setup means parents play an even bigger role in their children’s studies, Caballa said.

“Kung dati, hinahatid lang nila`yung bata [at] pinapasa na sa teacher, [ngayon] they realized [na] mahirap pala`yung ginagawa ng teachers, but at the same time we’re encouraging the parents [at] naka-alalay kami sa kanila (Before, they just dropped the kids at school. Now they realize that what the teachers are doing is not easy. At the same time, we’re encouraging the parents and we’re helping them.),” she said.

“It becomes less teacher-dependent because the teacher is just a facilitator and the parent is the lead teacher, which is how it should be.”

Caballa said she found comfort in how several learners have responded to the distance learning setup.

“For the majority, we found out that they were more resilient than how we had perceived them to be. We thought they won’t be able to adjust,” she said.

Running a private SPED school where parents shoulder the costs still has a lot of challenges, especially on the part of teachers, Caballa admitted. There are two backup teachers per session in case the internet connection falters.

“It’s difficult, but I guess we’re driven by our passion for what we do. We know that we don’t have a choice. The other choice is just to stop,” Caballa said. – PCIJ, September 2020

Winona Sadia finished AB Journalism at the University of Santo Tomas. She works as a TV news producer. You may reach her on Twitter (@winonymous) or at sadiawinona@gmail.com for comments or suggestions